You might have already met Alex at Arhiva de Cafea și Ceai in Sibiu. He left Ukraine because of the war. His story is quite interesting, he says, because he left the country on his own at the age of 17 in order to avoid being drafted into the army. “Who wants to die?” he asks rhetorically. “Basically, I didn’t have any other options. So I came to Romania because here, legally speaking, people under 18 can stay on their own without parents or guardians. In other countries, I’m not sure, but I think they would place minors in centers along with other children without parents.”

I got to know Alex better one evening in Piața Mare and asked him to share more about his experiences over the past few years. He told me that some people here refuse to talk to him because he doesn’t speak Romanian, even though he speaks English, one of the most widely spoken languages in the world. Reactions vary: some are open to dialogue, while others reject the new coffee options he proposes without even trying. Alex also speaks fluent German, and he says he has recently been improving his Romanian more and more. In his free time, he writes poetry.

We also spoke about the subtle ways racism can manifest, about how easily someone can be excluded simply for being seen as “the other.” It was difficult for him to process this emotionally, especially considering that he comes from a loving family, where he has never encountered violence in any of its manifestations. Yet Alex reminded me that everything can shift once you meet the right people — those who welcome you, listen to you, and make space for your story.

Alexandra Bene: Could you tell me a bit about the social context in Ukraine? What was your journey from Ukraine to Romania like, and how challenging was it for you to adjust to life here?

Alex Diachenko: Socially, I guess the answer would be the same. I was living on my own. Unfortunately, I only have my mother as family. I didn’t have any other choice. She stayed in Ukraine to take care of our family business — that was the only option. Settling here was actually okay, because I moved in with friends. I chose Sibiu since I already had a friend here who suggested we rent an apartment together. It turned out to be a really good idea, both emotionally and financially. It was truly a great opportunity.

AB: In what ways does war change a person’s life?

AD: With a bit of luck, the war didn’t affect me too much — not physically, not even mentally, at least not in ways I couldn’t handle. Still, I’ve realized recently that I lost part of my childhood, though not only because of the war. Before that, we had the coronavirus pandemic. I wasn’t going to school at all; everyone was learning online. Then the war started, and I lost even more contact with my friends. Everyone had their own problems. Honestly, I can’t even remember the last time I was in school — maybe in 9th or 10th grade. It was the same for university; I studied mostly online. So if there’s anything I regret, it’s losing part of my childhood and the everyday closeness with my friends.

But from where I stand now, I can also say these experiences made me stronger. I wouldn’t call it a good thing — war never is — but when life gets harder, you’re forced to grow up. Some people were broken by it, emotionally or financially, but for me, it was… manageable.

You start valuing things you never even noticed before. Like seeing an airplane in the sky — it felt like a masterpiece of art. I hadn’t seen one for a whole year before coming to Romania, and the first time I looked up and saw it, it was breathtaking, like fireworks. Or something as simple as going for a walk at night, or meeting friends who live nearby instead of across borders. Now, my closest friends are scattered in different countries, and we only manage to see each other once a year. That’s hard. And then there are parents, your home, all those things you take for granted — suddenly they become everything.

AB: How is the communication with your mother?

AD: We do chat online mostly. We recently saw each other in Bulgaria. Mostly, we see each other once in an year, in half a year.

AB: Can you tell me about your experience of integrating here? Were people welcoming to you? I know you also work at Arhiva de Cafea și Ceai — what has it been like for you to work as a barista?

AD: Generally, I don’t want to say anything bad, because I actually like Romania. But my first year here was pretty tough. People do understand our situation and try to support us, but from my point of view, Ukrainians in Europe don’t always make the best impression. They receive financial help from government programs and often stop there — they don’t want to get more involved, unfortunately. I can understand, to some extent, the prejudice I sometimes faced because of this. That’s why I started telling people I wasn’t Ukrainian — I would say I was British instead. With most new people I met, I would lie and say I was from Britain, just so I wouldn’t be labeled as Ukrainian.

As for working in a coffee shop, I think it’s one of the most fascinating businesses. I also really enjoy logistics — I’ve worked quite a lot in that field — but making coffee feels like a passion. I try to improve my technique every day, and for now, the experience is amazing. Still, I have to say, customer service in Romania can be a real challenge. I’ve worked in logistics, tax support, sales, and now coffee shops, and in my experience, it’s very hard to keep things running smoothly in Romanian business culture. For example, in logistics, I often saw international departments that didn’t function properly. If you call them, they might not even speak English — which is crucial for big companies. And then, of course, people point out that my Romanian isn’t perfect. Well, maybe not — but I do my best.

AB: In order not to feel criticized or excluded?

AD: No. Honestly, it’s the other way around. As soon as I say I’m Ukrainian, people react with a kind of polite sympathy — that quick ‘Oh, sorry!’ feeling — but then the conversation stalls. It’s hard to move forward from there. But if I tell them I’m from Britain, the reaction is completely different: ‘Oh, man! How do you like it here? What’s going on?’ Suddenly, the conversation opens up, and the whole dynamic changes.

AB: Do you feel that when you tell people you’re Ukrainian, they simply pity you and stop there?

AD: No, I wouldn’t really say that. There were a few moments like that, yes, but we all know you can find such people anywhere. I’m absolutely fine with it. For the most part? No — it’s not like that.

AB: Do you think this reluctance you’ve noticed — the lack of openness to dialogue or even the refusal to try a new café menu — comes from a kind of conservatism?

AD: I’d assume it has a lot to do with the kind of education that’s been passed down from generation to generation. Children are often not encouraged to try new things. There may be something you’d genuinely want to do, but in the end, you hold back. For me, that’s just sad.

AB: Are there cultural differences between Romania and Ukraine that you feel have held you back in some ways?

AD: I can tell you for sure that there are huge cultural differences, even though our countries are not so far apart. Ukrainians have also grown closer to one another because of the war. But in my mind, Ukrainians will always be the people I knew when I was 15 or 16, before the war began. We’re not exactly an open-minded community — we can be quite conservative — yet at the same time, we are capable of openness toward others. Somehow, I still find Ukrainians more enjoyable to be around, even though I haven’t been home for years.

AB: Was it hard for you to make friends here?

AD: Absolutely — for all the reasons I mentioned earlier. In my first year here, when I told people I was Ukrainian, it was really difficult to make friends. By the second year, it got easier, and now it feels easier still. At this point, I actually feel great when it comes to friendships and social life.

A lot has changed over these years. I’ve changed, too — my Romanian has improved, and that made a big difference. When I first arrived, I knew nothing about Europe, and nothing about Romania. But within a year, I managed to settle in. I began to understand Romanians better — what they want to hear, what they don’t — and that helped me connect with people.

AB: What are the things they like to hear, and what are the things they don’t?

AD: They don’t like to hear English, at least not at first. Every time I began a conversation in English, the answer was always: ‘Nu vorbim engleză!’ I was shocked, thinking to myself, ‘Wow, people really don’t speak English here!’ But that wasn’t true. They can, they just don’t want to. Maybe they’re not in the mood, maybe they feel insecure about their English, maybe it’s anxiety — I don’t really know.

But once I started using basic Romanian, simple phrases and conversations, everything became easier. I noticed something else, too: when you need something from Romanians, they don’t speak English; but when they need something from you, suddenly they do. Still, with my clients, communication is pretty relaxed — I hardly ever use English anymore.

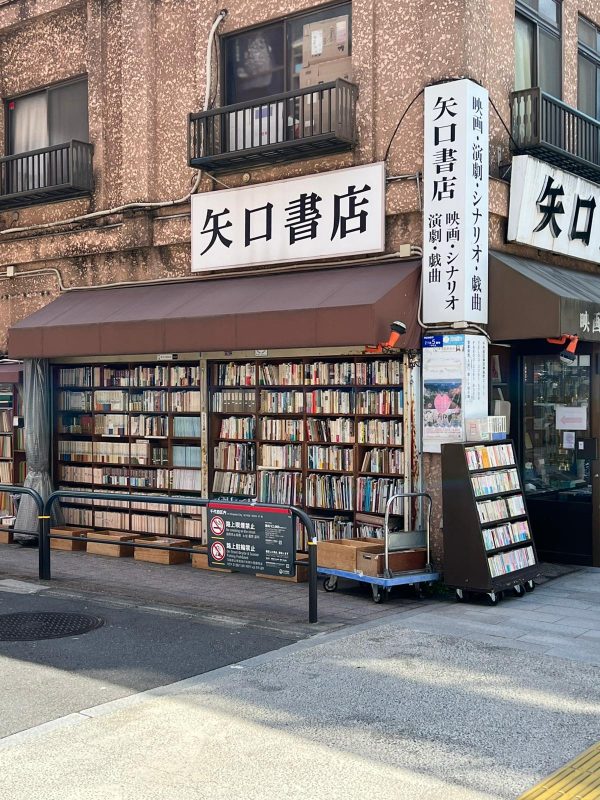

AB: Tell me something, please, about your trip to Japan.

AD: I’ve never been religious, yet in Japan I felt an unexpected need to pray in their temples. The atmosphere was filled with a quiet calm that seemed to settle over me. Standing there, among people so different from myself and immersed in a culture so unlike my own, I felt both surprised and deeply moved. Watching others pray, I suddenly wanted to do the same. It was a moment of pure admiration, and I savored every second. I know I’ll return the first chance I get.

What impressed me most, though, was the seamless connection between nature and technology. It reminded me of those futuristic images we all saw in school — skyscrapers with gardens inside, trees growing on the 50th or even the 100th floor. In Tokyo, that vision isn’t just a dream; it’s reality. Seeing it with my own eyes left me in awe.

And then there were the temples again — places that touch something deep within you, beyond reason or explanation. To be honest, I didn’t always feel comfortable with certain aspects of Japanese behavior and culture. But there is one thing I believe Europeans could learn from them: respect. If we embraced even a fraction of that respect in our daily lives, we might come close to creating a perfect society.

Personal archive

AB: What about the notion of respect among Romanians — both in how they treat each other and how they treat those from outside their society?

AD: One thing I can say for sure is that Romanians are respectful — all of them, really. Respect here is expressed in behavior, in the way people interact with one another. Looking back, I think my first year was difficult partly because I wasn’t surrounded by the right people. I had quite a few unpleasant experiences back then. But over time, I found a community and friends I truly value. They’re all Romanian, and they’ve shown me nothing but respect and kindness.

Of course, there were exceptions. I remember once sitting on a terrace at the mall, enjoying time with my friends, when a group of strangers came up and tried to insult me for no reason. That sort of thing, unfortunately, happened more than once during my first year here. But now, it doesn’t happen anymore.

AB: To what extent do we truly grasp the reality of what’s happening in Ukraine? Are there mental biases at play when we discuss the war?

AD: You really have no idea what’s going on there, unfortunately. The last time I told someone I was Ukrainian, their reaction was, ‘The war is still going on?’ Yes — it is. I don’t think Europeans are truly well informed. And the challenge lies in the news itself. Just as Russia has propaganda, so does Ukraine. These days, finding the full truth is incredibly difficult.

© Maia Loloiu